Suburbia: the dream that spread like an oil stain

A private garden, a pristine lawn, a house identical to the neighbor’s.

The promise of freedom framed by a white picket fence. The domestic utopia that grew between highways and shopping malls.

The Suburbia exhibition at CCCB guides us through that diffuse territory, somewhere between dream and nightmare, where comfort blends with loneliness, and the promise of well-being becomes a disturbing mirror.

There is something deeply revealing in walking through its images— its prefabricated houses, its happy families on the edge of the abyss, its cloned landscapes that we no longer know if they are real or fiction.

Suburbia is not just a place. It is a narrative, an ideology, a way of inhabiting the world. And perhaps, too, a warning.

Because Suburbia, in reality, does not offer freedom: it offers control

The supposed suburban autonomy was built on isolation, on the fragmentation of social fabric, on absolute dependence on the car,

and on cultural homogenization in service of consumption.

The dream of the “perfect home” was a political operation, a response to postwar social unrest, a mass-produced product designed to contain bodies, desires, and movements.

Beneath the veneer of comfort lies the domestication of space and time, surveillance disguised as safety, fear of the other, transformed into urban design.

Suburbia is also a gendered space:

the woman confined to the equipped kitchen, the spacious walk-in closet, the endless garden, while the man drives off to the office.

A paradise built on the repetition of roles,

emotional confinement, servitude dressed up as stability.

And above all, it is a form of expulsion.

Suburbia was never a model for the working classes, but a way to dissolve social conflict into individual plots, to replace collective struggle with mortgages.

A pacification disguised as upward mobility, a dispersal that fractures, dilutes, and isolates.

And yet…

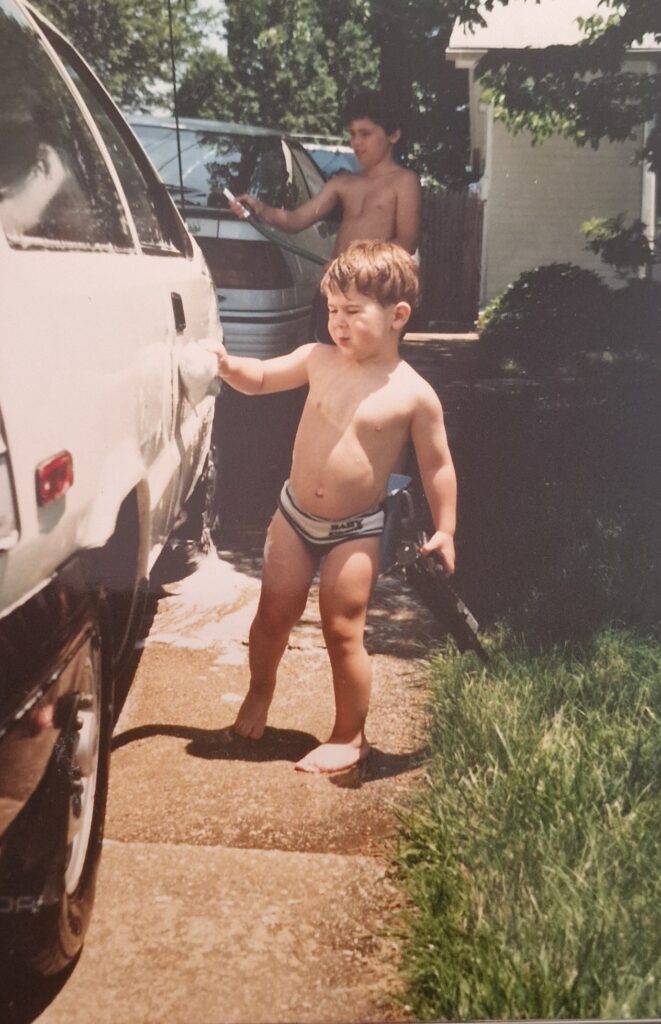

I have lived in suburbs. Not the ones from TV shows, nor those targeted by militant urban criticism.

Real suburbs, on three different continents: Cape Town, Canberra, Washington.

Middle-class and upper-middle-class environments, yes —I admit it without shame— but also places where I discovered silence, openness, stillness.

Where I could walk barefoot, breathe without noise, and look up at the sky.

It’s true that the car was everything, that distances were long and time often slipped away in transit, but it’s also true that, in those urban margins, I found a different kind of freedom, a more intimate relationship with nature, a space to imagine, to get lost, and to find myself.

And although people say there is no community there, I remember a childhood with open doors, children going from house to house, afternoons in the sun shared across gardens.

Suburbia, for me, was not solitude, but another form of companionship —softer, more diffuse, but real.

Today, from a distance, I recognize the fragility of that model.

Its beauty was built on privilege, on cheap land, on abundant energy. A low-density system that devours land, multiplies emissions, dilutes public life, and turns freedom into dependence: on the car, on consumption, on comfortable isolation.

It was never a model that included everyone.

It was designed to exclude, to scatter social conflict, to confine women in the idealized home, and to keep working-class people at a safe distance— offering wellbeing while deferring any real transformation.

This is my contradiction.

The critique is fair, necessary, urgent. But my experience doesn’t entirely fit within it.

Perhaps the problem is not the existence of suburbs, but the way they were designed: to pacify, to separate, to domesticate.

Perhaps we need to imagine other forms of dispersed living— more open, more shared, more human. More aware of the land they occupy and the future they risk.

And perhaps, too, we need to listen more closely to those of us who have inhabited them, to find in that blend of memory and critique a new way of dwelling.